Macro Cheatsheet

Long Read — How Important Stuff Works

To save anyone the trouble of doom-Googling background concepts in subsequent articles, I shall embark on a rather lengthy altruistic post addressing the relationship between macroeconomics and financial markets. You may ask, why bother with this stuff? To be like one of those guys? Douchebag guys. Ferragamo tie and bottle service guys. Talking about the DOW and EBITDA and shit. Bunch of fat cats eating other people’s lunches who aren’t even interesting humanist creative types or nerdy in any useful way like engineers or cancer scientists.

Bother, because whatever it is you do to pay the bills — be it cardiothoracic surgery or “challenging” COVID by tonguing toilet seats on TikTok — presumably, the goal is to get to a point where you’ve gathered enough shekels to have something called security. This makes your life better. You can do more stuff and deal with bad things that happen. It’s probably worth it then to be able to manage your pile of shekels intelligently. Or at least intelligently evaluate the actions of those doing it for you.

This one’s for you, noobie.

Cash Money

From Piggy Banks to Flowing Capital

In the beginning, God created the heavens, the earth, and lodged inside it lots of easter eggs called metals and hydrocarbons. Then these greedy monkeys called humans came along and decided they wanted more than berries and leafy shade. So, they organized their efforts (labor) and undertook activities (production) to help them service a perpetually expanding set of needs and wants. Labor and production were assembled around the following:

- There was a thing of scarcity — a hard-to-find nugget of copper or gold that was shiny and required resources to dig up.

- Which had an element of utility — to make spears and helmets to take other peoples’ shit, or decorate your hat so people knew you were important. To generally acquire resources more efficiently.

- Which was turned into a unit of exchange — a literal bit of that very scarcity stamped out into uniform king-faced units of weight to serve a basis to measure the value of everything else.

Money was born — as a shekel. Presumably, shekels could be melted down and turned into useful things like chisels or mallets, so it made sense that they were considered valuable. This money had intrinsic value.

For a vast stretch of human history, Hammurabi types voyaged their kingdoms with sheep bladders and ox carts full of shekels to get things done. Centuries passed. Eventually people realized shekels were pain in the ass — expensive to store and inconvenient and unsafe to transport.

Over the years across various civilizations — versions of influential Medici merchant types with ships and guards offered to store your florins (fancy Italian shekels) and issue paper guaranteeing their redemption on demand — a depository note. This paper represented a social contract between participants in the economy. These contracts were efficient and would become ubiquitous — evolving into an array of banking and credit instruments initially centered around trade.

This is key. The rise of intermediaries enabling trust-based systems was crucial to every facet of civilization’s progress.

Take broseph Mehmet — a paintbrush maker in Constantinople who intends to ship paintbrushes to broseph Michelangelo in Florence. Mehmet doesn’t know this broseph. But Banco Medici issues one of those bulletproof wax sealed scrolls guaranteeing his Florins on receipt of the goods — its game on.

Now, what other important thing does this accomplish? The ability for money to enable incentives across time. The value of trade could be exchanged prior to or after the actual exchange of goods. This too, was crucial in liberating commercial activity from static stores of capital.

These early instruments then evolved into legal tender in the form of banknotes — the ultimate social contract between citizen and sovereign. Money itself didn’t change for five millennia, but money and banking had been fused into a chemical bind well before current monetary systems emerged.

The ol’ Ball and Chain

By the industrial age, the prevailing monetary systems of the world were built on some form of a gold standard — paper backed by reserves of gold. Gold is not useful, but it doesn’t corrode and humans just couldn’t get enough of what it did for bodily décor.

The Bretton Woods System was the contemporary iteration of this model of money, under which you couldn’t actually redeem gold with dollars but slept soundly at night knowing it was in Uncle Sam’s coffers.

Bretton Woods was a post-war “new-sheriff-in-town” flex by the US requiring nations to ensure the convertibility of their currency at a fixed rate to the dollar and the dollar itself fixed at $35/Oz to gold.

The dollar/gold price-peg was the reserve mechanism under the gold standard.

So, the greenback was “as good as gold.” Bretton Woods drove demand for the dollar and ensured it maintained its buying power. The rampaging industrial machine that was the global economy of the 20th century propelled the production of goods and services to never-before seen levels.

By design, gold-based monetary systems blunted the tools available to support said growth, with the money supply beholden to the availability of a rock pulled out of the ground in Africa and South America (or China and Russia).

It took less than 30 years for Tricky Dick Nixon to abolish Bretton Woods. Spurred by a rise in the US trade deficit and budget deficit due to the Vietnam war, the circulating dollar supply had ballooned to around five times its bullion backing.

In 1971, the US Dollar became a floating currency. Meaning it was now a market instrument. Its price determined by the market equilibrium of demand and supply for dollars, expressed in terms of a floating rate against another currency.

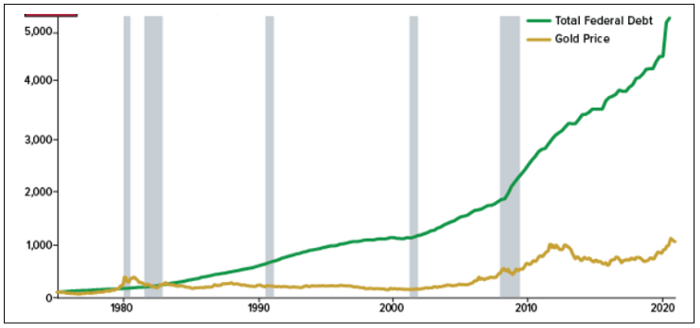

US Fiscal Expansion Since the Gold Standard — Source: US Treasury Department

Show Me the Value

Today, you cannot turn up to the US Treasury’s offices and request to swap your bucks for bling. Instead, the greenback is backed by “the full faith and backing of the US Government.” Now that might sound like a bunch of balls some Leviathan despot might say.

Money does after all represent the ability to engage the world’s finite resources. How can its production be subject only to the laws and objectives of Americans — a species with a proven insatiable quality to acquire and consume. Is money not the very thing that needs a natural anchor?

Well, yes and no. The flaws of the gold standard became apparent as the global economy expanded:

- Gold is a finite commodity. In principle it cannot grow in tandem with the real economy, making it a deflationary force. Inflation would have an upper limit equal to the rate of production of new gold supply.

- Gold miners could effectively hold central banks hostage.

- The gold-dollar peg meant that gold market volatility would reverberate into the cost of all goods and services.

A modern market economy is arguably not very well suited to fix up to some extraneous quantity. The social contract itself can be seen to have intrinsic value if market forces deem it so. The idea is no more absurd than a monetary base comprised of a stash of rocks that do little more than glimmer and cost an arm and a leg to dig up and safeguard.

Imagine your dollars were rare earth metal shekels which you could melt down, take to Tim Apple and ask for an iPhone. What then, of the rare earth metal mining co. that supplies these metal shekels by the boatload enabling the production of iPhones at scale at an affordable cost? The price of that shekel cannot be the same as your shekel. Without a degree of independence, money loses its fungibility. Something that gives it utility — a determinant of value.

So, the dollar is still just a piece of paper. In theory there is no guarantee of its ability to acquire resources of a determinant value. Now let’s say you found a clump of purple goo that’s 1 of 10 in the world. Let’s assume said purple goo does not power your car or moisturize your skin or do anything useful.

The price of purple goo will be nonzero in the absence of obvious, direct utility for one reason — someone can in turn exchange the goo for something else. In other words, there is prevailing adoption.

Black — the New Gold

So, the US had learned fixing the price of money to a commodity is not fun — especially one that doesn’t do anything. There was however a commodity that did pretty much everything which nations were constantly falling over each other and going to war to try and secure.

Within a couple of years of dropping gold like a hot potato, for their second trick — the Nixon administration had shuffled off to Saudi Arabia and enter a series of agreements which spelled the birth of the petrodollar. There is an important distinction between the gold standard and the petrodollar:

The dollar, instead of a price-peg, was fixed as the standard unit of exchange for crude oil

The global trade for oil (estimated today at $4 trillion) would be conducted in US Dollars after 1973. Every country in the world needs oil, hence they were going to need a stock of Uncle Sam’s social contract.

The petrodollar achieved the same goals of Bretton Woods — ensuring the demand and buying power of the dollar, but without constraining the money supply and monetary tools of the US government.

Inflation in the US economy would dictate the buying power not just the US, but anyone who had to purchase oil. When the oil price moves, most other currencies realign to the dollar. Today, almost 90% of all FX transactions involve the dollar.

Oil producing nations pegged their domestic currencies to the dollar to ensure the dollar-denominated profits from their primary moneymaker remained stable.

The US itself constantly ran a trade deficit as the petrodollar maintained its buying power vs other currencies. Capital flows into the US were cheap and plentiful, but the tradeoff meant the factors of production were cheaper elsewhere. This facilitated the growth of offshore manufacturing which gave rise to China-style economies.

Developing nations buy US government debt with excess dollars (think China), and issue US-denominated debt to fund its deficits. Foreign debts of developing countries (not including oil producers) grew by an average of 150% in the five years following the conception of the petrodollar.

The dollar found its way onto the balance sheet of pretty much every country in the form of US-denominated assets, US-denominated debt, and holdings of dollars in the form of reserves. Almost 60% of the FX reserves held by all nations today are in dollars.

It has become eerily reminiscent of the gold standard. Exporting nations covert trade surpluses to dollar reserves or US treasuries. Nations with trade deficits experience dollar outflows causing fiscal and monetary issues. The dollar is today the reserve currency of the world.

US Dollar Share of Global FX Reserves — Source: Bloomberg

Dollar dominance isn’t all about access to oil though. Take gold — Investors today still befuddlingly desire it as some random hedge against inflation (a fall in the purchasing power of money) because of its history as a control variable.

This is demand by association with little else to determine its value, except scarcity — which is a state of supply, and not in itself a driver of value. Yet demand for gold drives a market price that outweighs the headache and cost of its acquisition and storage. Adoption can prevail organically if there is a preexisting influence over global factors of production.

The New Ball and Chain

The gold standard and petrodollar are examples of how adoption can be enforced. They helped create a world where the dollar is now deeply implanted in public finances, global trade, and commodities markets. It is the de facto medium of exchange for goods and services across borders.

But the underlying basis for dollar prevalence has always been its designation as legal tender to pay the taxman of the most powerful overlord on earth. There are 330 million yanks each earning an average of over $63K. That spending power is taken very seriously by anyone selling anything anywhere in the world.

It is the richest collective population, representing 30% of global wealth and 24% of the world’s energy consumption. The most valuable companies are American with a collective share of over 40% of the market capitalization of global equities.

Dollar dominance is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Even if its foothold wanes (as it has been in certain markets), the value of the dollar is equated with US superstrength and conflated with the future economic output of the United States.

When the US did away with the gold standard, the supply elasticity of the dollar became theoretically perfect. Today, there are no extrinsic constraints on the US Government’s ability to maneuver the supply of money — only incentives.

The Federal Reserve (the Central Bank of the United States) is in charge of the dollar xerox which is part of its toolbox to administer monetary policy — a set of tools available to a government for controlling economic growth via the money supply.

Why would you ever want to temper economic growth? Inflation.

It’s been kind of an issue lately. You may have noticed frozen chicken at the supermarket priced like its Thomas Keller’s coq au vin. If not — good for you, baller.

It is the Goldilocks thermometer that inevitably pips too high making your average broseph’s porridge unaffordable. Sales of porridge decline, and Goldilocks Inc the porridge company fires many a broseph.

Lord Chairman Powell of the Fed does not like this.

Fractional Reserve Banking

So now we know what money is and what it does. Now, let’s see how it moves.

Credit is economic fuel. For a household or firm to expand its economic universe i.e., its balance sheet, it needs capital to purchase assets and increase its capacity to generate economic value. Your average broseph needs a boost to buy that rental property or an oven for his new pizza joint.

Capital is composed of either equity (cash in the coffers) and/or debt (credit against future return on that capital). Debt is cheaper. In modern finance it is considered imprudent to not maximize serviceable debt (with a margin of safety) in the capital structure.

A bank’s balance sheet appears inverted to that of a regular company. A loan (liability) for Broseph Pizza Co. is an asset for a bank. A cash deposit (asset) for Broseph Pizza Co. is a liability for a bank.

Banks happen to have an additional unique mechanism to scale.

The Fractional Reserve System

The term describes the current banking industry in the context of a set of regulations requiring only a fraction of bank deposits to be backed by actual cash. The fraction is expressed by a Reserve Ratio set by the Federal Reserve — the regulator of the banking system. The bank takes a percentage of the cash from its deposit liabilities, and places it with the Fed as a reserve. That reserve becomes an asset for the bank, and a liability for the Fed.

Let’s say the Reserve Ratio was 10%. It would mean if $100 were deposited into the banking system, $10 would be the Required Reserve, which had to be deposited with the Federal Reserve. The remaining $90 is considered an Excess Reserve, and available to loan out. If a bank loans out the $90 and that loan is then deposited back into the banking system, presumably the process could be repeated as demonstrated in the following table:

The theoretical upper limit of new money created per $1 deposited in the banking system is called the Money Multiplier, denoted by M in the below equation where R is s the Reserve Ratio.

M = 1/R

The result in theory is that assuming a 10% Reserve Ratio, every $100 deposited would result in $900 of new money created under the fractional reserve banking system. This is the mechanism the Fed looks to trigger with monetary policy tools, and is the basis for is culturally termed as “printing money.” Let’s dive in further. The different measures of the money supply now become relevant:

Monetary Base (MB) = Reserve balances at the Fed + All currency in circulation.

M1 = Physical Currency + on-demand instruments (current accounts, travelers’ cheques etc.).

M2 = M1 + Time contingent money (term deposits, money market fund balances etc.).

M2 is a broader measure of the money supply that actualizes over time and the difference between M1 and M2 can serve as an indicator of inflationary pressure in the economy. In practice, not all excess reserves are loaned out and not all loans are deposited back into banks. There is significant leakage from the banking system. To determine the Actual Money Multiplier (AMM) which is the true measure of new money created under the fractional reserve system, we calculate in reverse using the existing values of the money supply:

AMM = M1 / MB

Here is an excellent resource from the generally excellent Khan Academy to dive deeper in to the Money Multiplier.

In 2020, the Fed set the Required Reserve Ratio at 0%. Hence all reserves currently held are considered Excess Reserves. This is not as crazy as it sounds.

The 0% requirement has in fact, proven to be a functional policy when taken in tandem with other regulations and incentive mechanisms to maintain reserves with the Fed. The reserve base has increased dramatically since the 2008 financial crisis as the Fed began offering interest on reserve balances during that period.

Excess reserves are also factored into a bank’s credit rating, which helps improve the cost of acquiring liquidity from the market. Banks have an incentive to park their funds with the Fed to improve the quality of their balance sheet.

It is important to note that reserves still represent a liquidity trade-off for banks, as they represent high quality liquid dosh — little Ferragamo tie wearing soldiers — seeking to earn the best risk-adjusted yield.

Other core regulatory metrics play a major role in the absence of a minimum required reserve. Minimum ratios for Capital Adequacy and Liquidity Coverage are enforced by the Fed in tandem with a 0% Reserve Ratio to uphold the same principles as higher reserve requirements.

Remember that the Reserve Requirement only pertains to the proportion of deposits that must be held in cash. Liquidity and Capital encapsulate the wider balance sheet.

Liquidity: Is a measure of the extent of a bank’s ability to handle short term obligations — which is the net impact of cash flowing in and out of the bank. Suppose on any given day two things occur:

- Asset: Joseph makes his monthly mortgage payment of $2,000.

- Liability: Broseph withdraws $3,000 from his current account on his way to the clurrb.

— — The bank’s liquidity position contracts by -$1000.

Liquidity is regulated via the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR):

LCR = Liquid assets (cash, bonds, marketable securities) / 30-day cash flows (stress tested)

Liquid assets must also be deemed “high-quality” and are excluded from Required Reserves because they must be available for meeting liquidity shocks without compromising the Reserve Ratio. With a 0% Reserve Ratio, the stock of Liquid Assets kept in Excess Reserve deposits are available to meet regulatory requirements increases.

Capital: Is the difference between the bank’s assets and liabilities — or its net worth (this isn’t the same for regular companies where capital is just one component of net worth). It is a measure of longer-term financial health. Suppose interest rates rise:

- Asset: Joseph loses his job and can’t afford to pay back his $500K mortgage loan.

- Liability: The bank must pay an extra $100K in interest on the huge balance in Broseph’s savings account.

— — The bank’s capital shrinks by -$600K.

Capital is regulated via the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR):

CAR = Capital / Risk Weighted Assets

A risk weighting classifies assets based on credit risk. Let’s take the example of $100K worth of different assets:

- Unsecured loan to a small business: This is deemed high risk so 100% risk weighting would mean allocation of the full $100K toward the denominator.

- Mortgage: Lower risk due to recourse on real estate would have a 35% risk weighting, meaning an allocation of $35K.

- Cash: Zero risk, 0% allocation.

The numerator (Capital) is also classified as either Tier 1 (consisting of shareholder’s equity and retained earnings) or Tier 2 (consisting of various equity reserves, quasi-equity instruments and subordinated debt). Tier 2 capital is considered more difficult to liquidate hence there is a separate requirement for a Tier 1 CAR.

The banking industry is more regulated, audited more frequently, and has a daily requirement to reconcile its liquidity and capital positions.

When shit hits the fan like it did in 2007/8, what can result is a run on the bank — higher than usual withdrawals that it cannot handle.

Any instance of your average broseph not being able to tap his account balance at will is a death blow for a bank’s business.

Even in the absence of a required reserve, banks ensure the availability of funds to their depositors and their overall ability to deal with shocks. First and foremost a bank is a safekeeper. Credibility is incredibly hard to salvage.

Anatomy of the Monetary System

Don’t Hate the Playa

To lay the groundwork for how and why monetary policy works, we must acquaint ourselves with the major players in the game:

- The US Department of Treasury: These guys are bookkeepers. They manage the cash flows of the US federal government. They collect taxes and pay the postmen. The US Mint falls under the US Treasury so this is the entity that can actually “print” new money in the literal sense. Importantly for our purposes, this is the entity that behaves as the issuer and obligor of US government debt, which is primarily comprised of market-traded bond instruments. US Treasury securities are the primary instruments utilized to carry out monetary policy objectives.

- The Federal Reserve (Fed): The Central Bank of the United States, comprised of a collection of regional reserve banks overseen by a board of governors currently chaired by Jerome Powell. It is the regulatory and supervisory authority of the US Banking system, as well as the depository institution where bank reserves are maintained. The Fed acts as an agent for the US Treasury. It has the mandate to conduct US monetary policy which it executes primarily through market incentives for the banking system, and the sale and purchase of securities via an independent balance sheet. It is by a mile the most powerful financial institution in the world. It’s Chairman, Jerome Powell, moves trillions in capital with his every choice of verb.

- Depository Institutions: Mainly banks, overseen by the Fed. These are corporations with special privileges and unique accounting mechanics, that are also subject to more stringent regulation and oversight. Remember, a bank’s balance sheet appears inverted to that of a regular corporation. They are participants in exclusive money markets that support the exchange of liquidity, reserves, and securities to facilitate the wider economy.

So the Fed is (1) an agent the US Treasury, and (2) itself a bank holding the deposits (reserves) of other banks. The relationship between the Fed, the US Treasury and banks is captured on the Fed’s balance sheet:

The Bloat Here is Great

Fed Assets:

US Treasurys: (Bonds, T-Bills, T-Notes, TIPS) Collectively they are the designated “risk-free” assets of the world. The yield on these instruments represents the return for taking the least amount of financial risk available anywhere on earth. Everyone holds these things with the investor base encompassing sovereigns, institutions and households. $24 trillion in Treasurys are outstanding as of September 2022, ranging in tenor from a few days to 30 years, across various types of debt instruments. The Fed buys and sells existing Treasurys from the secondary bond market (and happens to hold a third of the whole kaboodle on its own balance sheet already courtesy an expansionist romp over the last 15 years).

Source: NY Fed

The Fed holds roughly $9 trillion in bonds. $8 trillion of which it purchased after the 2008 financial crash. We will shortly explain in detail the motivation behind this.

It should also be noted that Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) also represent a major Fed holding (almost $3 trillion). You might remember that term as the evil incarnation of Wall Street greed that sank the global economy as narrated by Matt Damon. Well, partly. And the Fed did spend the next few years buying up MBS from the market, which pumped liquidity into the economy (we will cover how below).

However, we aren’t going to delve too deep into this topic because there’s enough to chew on with Treasurys alone. Now to the other side of the Fed balance sheet:

Fed Liabilities:

Treasury General Account (TGA): Represents the cash hoard of the United States Government. The TGA serves as the operating account for the federal government’s budgetary activities — collecting taxes, funding highways and wars, issuing COVID cheques, paying the White House gardener etc. TGA balances are spent on goods and services and add liquidity to the economy. Historically, the TGA has not held excess funds because there is little point in keeping cash idle and the US Government has a bevy of obligations and budget programs that need servicing. When the TGA increases — i.e. the US Government raises money (whether through bond issuances or tax hikes), cash flows from investors and lenders in the economy to the US Treasury — the money supply contracts. When TGA balances decrease (Government spending), the opposite occurs.

It should be noted that the US Treasury’s balance sheet or the TGA is not impacted by the Fed’s monetary policy because it acts as a depositor with the Fed as its bank. The TGA is a source of funding for the Fed in the form of a liability on its balance sheet under the fractional reserve banking principle.

If the Fed purchases Treasurys from the market, it becomes a bondholder i.e. the US Treasury owes the Fed the Principal + Coupon at Maturity. When a bond matures, the US Treasury pays out the holder, and the debt disappears. The issuance and settlement of Treasurys is a separate operation and not to be confused with the buying and selling of Treasurys from the open market.

Bank Reserves — Interest bearing deposits representing required and excess reserves of banks. In the absence of a required reserve, banks still keep capital with the Fed and are incentivized to maintain liquidity in Excess reserves through interest rates offered on Fed deposits. These deposits serve as a source of funding for the Fed in the form of liabilities.

- If Reserve balances go up, it means the Fed is buying bonds from investors. Proceeds of these purchases are deposited into the reserve accounts of banks (who act as seller or seller agents) giving them a larger deposit (and reserve) base, providing new liquidity to splash out into the economy.

- If Reserve balances go down, it means the Fed is selling bonds to investors. Payments against these sales move out of bank excess reserve deposits (representing investor funds) held with the Fed. Cash is taken out of the economy.

So, when the Fed wants to add some life into a limp dead-ass economy, it starts buying securities. When it wants to tame inflation, it starts selling securities. But word on the street is that monetary policy involves controlling the interest rate. How does that fit in?

Fed Open Market Operations

The Fed purchases or sells Treasurys on a mass scale — enough to influence the market price of these securities.

We should run through some fixed income basics for the uber-noobies out there. Bonds are are IOU’s representing a principal sum to be paid back in (t) years with a kicker (coupon) for the trouble, the amount of which accounts for risk and time.

Why does buying and selling bonds change the interest rate? Because the market price of bonds and the yield they generate are inversely correlated. Let’s run through an example using a Treasury security:

- US 52 Week T-Bill

- Par value (Principal Amount): $100K

- Coupon (Interest): 3%

- Maturity: 1 year from now

An investor (lender) gives the US Government $100K in return for a Treasury Bill (bond) — paying $103K back in one year. A 3% return (yield) on his investment of $100K.

Note: In reality short term Treasurys are zero coupon bonds auctioned at issuance below par value, but forget that for now.

Remember, these are market traded instruments with an initial value (price) of $100K. Now suppose the Fed starts buying up these suckers like its Black Friday. Demand goes up, supply stays the same, so price goes up. That $100K bond is now trading at $101K.

If you buy the bond now from the market, your $101K investment is returning $103K in one year. Return falls from 3% to about 2%. This return is called Yield — it is the interest rate accounting for both the coupon and the market price.

Buying a bond is the same thing as lending. Bond = Loan. The return an investor or bank would receive in any given market environment. Hence it dictates the interest rate at which they are willing to lend to the wider economy.

We know that bond prices and interest rates are inversely correlated under the formula for Yield to Maturity:

Suppose the Fed, under an expansionist program is buying securities to pump liquidity into the market. The market price of a Treasury rises from $100 to $101. Suppose an investor is already holding the Treasury which was purchased at par value of $100.

The investor now has the choice to sell in the market at the premium, book a $1 profit, and reinvest the funds in an investment grade corporate bond trading at $100, offering at least the same or better coupon. This is often what happens causing yields in the wider bond market to move in the same direction as Treasurys.

Conversely, if enough investors do not do this, it causes a widening of the Credit Spread. The Credit Spread is the difference between the yield on Treasurys and corporate bonds. The spread gauges investor sentiment. If investors are bearish, they will swap risky investments for safer ones, causing the spread to widen. Conversely, if investors are bullish, they are more likely to seek higher yields by taking on credit risk over a risk-free investment (Treasurys).

Bond Market Credit Spreads — Source: Allianz Research

In the above table, “Investment Grade” represents the spread between 10-year US Treasurys and Investment Grade Corporate Bonds. The high yield credit spread represents the differential between Investment Grade and Junk bonds and follows the same principles reflected into riskier parts of the market. The VIX is the Volatility Index.

Since the Fed is likely to move the market in accordance with the prevailing economic climate, this cycle of investor activity is reinforced:

- Bullish Climate — Fed is buying bonds — interest rates fall — investors put cash into risk assets.

- Bearish Climate — Fed is selling bonds — interest rates rise — investors pull cash out of risk assets.

To sum up:

There is a trade-off between fiscal agenda of the US Government and the monetary tools available to the Fed. For example, in the current environment, the Fed is busy tackling soaring inflation. Its goal is to effectively pull liquidity from the economy (reduce the money supply). At the same time, Congress has approved a $1.5 trillion student loan forgiveness program which behaves as a massive stimulus, pumping cash into the economy.

Conversely, when the Fed is expanding its balance sheet, it has become culturally known as:

- Quantitative Easing

- Expanding the (M2) Money Supply

- “Printing Money” as a misnomer

In the current climate, Fed open market operations have become less effective as a stand-alone practice. There has been over a decade of monetary expansion after the financial crisis which was accelerated when COVID hit. The Government’s stimulus program (the largest in history) pushed TGA balances to almost $2 trillion (which was unheard of previously). At the same time the Fed began monthly bond purchases of around $100 billion. Banks are now flush with excess reserves. Under this “ample-reserves regime” the Fed is employing more direct tools involving the same underlying principles.

Direct Monetary Policy

This part gets pretty mechanical and at this point I’ve given up trying to be entertaining. But if you stick it out, well you’re just a special kind of noob.

Now that we know the composition of the Fed’s balance sheet and what open market operations entail, we can understand what happens when Lord Chairman Powell announces a change in interest rates.

The Fed Funds Market

Contrary to popular assumption, when the Fed announces a rate hike, it isn’t exactly like calling out bingo numbers…

Monetary policy utilizes the market mechanism to achieve its goals. The FOMC (Fed Open Market Committee) meets twice a quarter and decides on a target range for the Fed Funds Rate. This is announced to the world. Markets spaz out. Then the Fed gets to work implementing its target.

(if you trade you may have seen the FOMC Meeting as a 3-star/Red flag/Fire Emoji level important event on whatever trading calendar you use)

Markets tend to price in this target rate before the Fed undertakes the operations required to reach the target.

Fed Funds Rate (FFR): The short-term interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans to fund reserve balances.

Bank balance sheets are constantly changing with deposits and loans being issued, repaid, written off etc. At any time, their reserves could dwindle, while other banks’ balances with the Fed could hold excess reserves. These positions are reconciled daily.

And since we have learned that all bank deposits aren’t sitting in a vault somewhere like shekels, these requirements are met in various ways. One way is through short-term borrowing from the Fed Funds Market — a very liquid interbank money market where banks borrow and lend liquidity from a pool of excess reserves.

Reserve balances serve as a funding pool for operational requirements and interbank payments and are hence routinely funded and utilized.

Banks also earn interest and improve the quality of their balance sheet when they hold excess reserves, hence there is significant daily demand for Fed reserve deposits.

The Fed targets this rate because:

- Change in the FFR dictates changes in the level of bank reserves which guides liquidity (credit) available to the rest of the economy.

- Change in the FFR influences the rates banks charge for loans and savings offered to the rest of the economy.

“Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

The target FFR is expressed as a range. Within the FFR range, the actual prevailing market rate at any given time is know as the EFFR or Effective Fed Funds Rate. The range consists of three other money market rates that control the FFR to float within target levels which include the following:

The target FFR range follows a floor and ceiling structure with the IORB mainly utilized to technically adjust the EFFR as it drifts to the higher and lower ends of the range. This is known as Floor System of Monetary Policy which evolved from a need to adapt to the ample reserves environment which prevailed after the 2008 Financial Crisis.

Although all the above rates available to banks represent highly liquid, low risk money markets, all else being equal, banks prefer transacting with the Fed and prefer secured lending and unsecured borrowing. This should shed light on market expectations of the rank order and spread on this range.

- An administered rate is one that is directly set by the Federal Reserve through a “technical adjustment.”

- Market rates are guided by Fed Open Market Operations and administered rates.

- Note these are all overnight (very short-term) rates.

- Secured means loans collateralized by US Treasurys (Repos: discussed later).

We will explore the motivation behind the structure of the range later. Now we should address each component of the range in more detail:

Federal Discount Rate

The discount rate is the most attractive source of funding for banks, who would rather avail funds from the Fed vs other banks and would rather avail clean funding over funding secured against bond holdings or specifically to fund excess reserves. No bank would borrow from another bank at a higher rate than it could avail unsecured funding from the Fed.

Borrowing Bank’s Preferences:

Counterparty = Fed ˃ Interbank

Market = Unsecured ˃ Secured

The Fed sets this rate at the top of the range to encourage funding activity linked to excess reserves and the bond market at cheaper levels. This helps drive the Fed’s policy objectives. It has been lowered in the past in times of crisis when the Government assumes its role as a “lender of last resort” to the economy.

In practice, borrowing from the Fed at the Discount Rate may signal to the market that the borrowing bank is distressed. Hence there is usually an added reluctance to avail this rate.

Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB)

The deposit rate paid by the Fed to banks on their reserve balances. The IORB has become the primary tool in the Fed’s monetary policy toolkit, hence we need to spend some time understanding the IORB.

Assume a Bank has a static deposit base of $100 currently held as an Excess Reserve with the Fed. These are these are large pools of cash. Primo liquid assets (as is the requirement of reserve deposits). Little Ferragamo tie wearing soldiers that will seek the best risk-adjusted yield. The bank has the following simplified choices:

Recall the Money Multiplier discussed earlier. Lending amplifies the money supply because it creates new deposits. The IORB acts as a direct incentive to keep funds parked in Fed reserve deposits.

The above illustrates the incentives IORB adjustments create in the Fed Funds Market in a vacuum. Now consider a different state of the world where the IORB sits in relation to the Effective Fed Funds Rate (EFFR). Remember:

- IORB is the rate banks earn to lend Excess Reserves to the Fed

- EFFR is the rate banks earn to lend Excess Reserves to other banks

When the IORB is higher than the EFFR, banks have a choice of where to allocate their Excess Reserves: (1) lend (deposit) to the Fed at a higher rate or (2) lend to other banks at a lower rate. No bank will choose to lend to another bank at a lower rate than they would lend to the Fed. Supply of excess reserves available to borrow would dry up, causing the EFFR to rise.

There is also upward pressure on the EFFR because an arbitrage exists in this scenario for banks to borrow from the fed funds market and deposit Excess Reserves to earn a risk-free spread. If we take the example of the current market, where IORB is 2.40% and EFFR is 2.33%, the current payoff is negligible at around $2 per $1 Million. Market participants would very quickly eat up any meaningful spread available. Hence, when the IORB is above the EFFR, it ensures the EFFR follows the IORB very closely.

When the IORB is lower than the EFFR, banks can earn more interest on their Excess Reserves by lending them to other banks in the Fed Funds Market. The supply of Excess Reserves available to borrow would increase, putting downward pressure on the EFFR.

When Excess Reserves are abundant (like in the current scenario), demand for Excess Reserves is driven more by market incentives than other requirements.

- Banks are willing to lend Excess Reserves at or above the IORB.

- Banks are willing to borrow Excess Reserves at or below IORB

The Fed’s objective currently is to shrink its balance sheet; hence it is actively trying to prevent the creation of new bank reserves. Setting the IORB above the EFFR encourages banks to maintain their reserves and discourages lending in the Fed Funds Market, preventing the expansion of the monetary base.

IORB adjustments are the most effective tool available to the Fed because they accomplish two separate goals in isolation of the other: (1) It corrects the EFFR in line with the Fed’s target FFR range (as EFFR follows the IORB precisely) and (2) Incentivizes or disincentivizes expansion in the monetary base. Effectively disconnecting the direction of interest rates with the money supply.

In the current scenario, an attractive IORB in tandem with a resulting higher EFFR disincentivizes banks from borrowing or lending in other money markets and sets the cost of credit for the wider economy in line with the Fed’s objectives. The IORB would however not be so effective in an environment of low reserves as we will learn later.

Overnight Reverse Repo Rate (ON-RRP)

The final component and the sub-floor in the Fed target range is the rate on Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreements (ON-RRP). This is a secured overnight rate banks receive for lending funds to the Fed against Treasurys. The transaction takes the form of a Reverse Repurchase Agreement known as a Reverse Repo.

ON-RRP transactions have become an increasingly effective supplementary tool to the IORB and Open Market Operations. They are known as Temporary Open Market Operations. Like Open Market Operations (discussed earlier), both utilize the Fed’s balance sheet to modulate the monetary base.

Price Discovery: The ON-RRP rate can be considered a semi-administered rate as it is determined through an auction mechanism. The Fed established a Standing Repo Facility (SRF) in July 2021 — the size of which determines the daily capacity for transactions.

Investors (lenders) submit bids which are sorted by offer rates and ranked lowest to highest. The highest bid in the pool equal to the SRF capacity (assuming demand exceeds capacity), becomes the awarded ON-RRP rate for that day. It is estimated that current daily volumes in the ON-RRP market are least $2–3 trillion. Demand is high and bids are competitive hence the award rate has ended up below the bottom of the Fed’s target FFR Range.

ON-RRP and IORB are both windows to allow banks to lend to the Fed. Reverse Repos however have the added lure of also being secured by US Treasurys. Hence ON-RRP Contracts represent the highest quality assets a bank can have on its balance sheet. Banks have no incentive to lend to any market at a lower rate than ON-RRP.

The ON-RRP market represents a collateralized loan with zero credit risk and duration (time factor which, which drives up other money market rates as it increases).

Near quarter-end reporting dates, banks seek to minimize the risk on their balance sheet. During these times funds tend to flow from Excess Reserves and the Fed Funds Market to the ON-RRP market.

The use of ON-RRP by the Fed has grown significantly as they pivoted policy in late 2021 to tackle inflation.

The growth of the Fed’s Reverse Repo balances from virtually nonexistent to over $2 trillion is a sign of excess liquidity in the banking system. It demonstrates that banks have ample cash to spare after meeting liquidity and other requirements and have a significant appetite for low-yield Fed money market transactions.

If the market moves the EFFR to the bottom of the target range, the Fed can do two things to coax it back up: (1) raise the IORB (widening the EFFR/IORB arbitrage spread) or (2) raise the ON-RRP to set a hard floor for the EFFR.

Access to the Fed Funds Market and the IORB is restricted largely to banks. The Repo market is however available to other financial institutions including Money Market Funds (MMFs) representing $5 trillion in Assets — 30% of which are held in Repo markets. By lending to the Fed through Reverse Repos, MMF investor funds flow from bank deposits into the Fed’s money market fund which locks up liquidity overnight.

Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR)

The interest rate charged on overnight interbank loans secured by Treasurys, also known as Repurchase Agreements (Repos). SOFR is also known as the Repo Rate. It is outside the Fed’s target range because it has no direct link to the Fed’s balance sheet.

SOFR is used in the interbank Repo market where MMFs and other Financial Institutions also participate. These participants have a choice between earning the ON-RRP rate through Treasury-backed lending to the Fed or earning SOFR through Treasury-backed lending to other financial institutions.

The Repo Rate can be interpreted as another (market-driven) floor to the EFFR because no bank would lend unsecured funds at a lower rate than secured funds. At the same time, the Repo market is not specifically for funding reserves. Although increasing reserve balances serves as a source of funding for banks in general, the Repo market serves as a source of funding for other Financial Institutions meaning it should have a larger demand base.

SOFR higher than ON-RRP:

- Less incentive for lending to the Fed

- Increase in interbank lending

- Liquidity in the market goes up

SOFR lower than ON-RRP:

- No incentive to lend in interbank market

- Fall in funds available for banks to borrow

- Liquidity in the market goes down

There also exists an arbitrage if SOFR is sitting below ONRRP. Borrow from the Repo market and lend to the Fed in the Reverse Repo market. Or if Banks can afford to tie up their collateral they can borrow from Repo and lend in the Fed Funds market or deposit at the IORB.

The collateral factor is however significant. In an environment with excess reserves banks have a strong appetite for quality collateral (Treasury securities) and a shortage in collateral results in yields being driven down. So, if ON-RRP is kept above SOFR to drain liquidity there is a risk of it counteracting another element of the Fed’s Open Market objectives.

SOFR was “chosen” as the market standard benchmark rate for lending to the wider economy by the Fed because it cannot interfere with monetary policy objectives sitting outside the target range. However, it still follows the Fed’s target basket of rates closely as it is subject to the same drivers.

To bank customers, this rate is known as the benchmark rate. It is expressed as a sum of Margin + Benchmark.

- Margin = Credit spread based on a measure of the risk factors associated with the underlying customer or asset in terms of the loan structure.

- Benchmark = A standard minimum base money-market rate. Previously denoted by LIBOR (London Inter-Bank Offered Rate) and now by SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate)

Note: LIBOR has been used since 1986. It is the benchmark rate (or the basis of other benchmarks around the world) for most of the loans, bonds, derivatives and financial instruments outstanding today (over $350 trillion). This rate was established periodically through a survey of major banks based on their expectation of future borrowing cost. It ended up being manipulated at a mass scale by colluding banks who would submit artificially low LIBOR rates to jack up the profits of their trading desks who held positions in LIBOR-based instruments. LIBOR is currently being transitioned out and replaced by SOFR.

The above chart shows the current hierarchy of money market rates in the Fed’s range window of 2.25–2.50%. Technical adjustments of the IORB control the lending rates almost basis point for basis point. These adjustments are supplemented by open market operations and reverse repos.

The two rates highlighted in yellow are Fed-Administered (IORB — through direct adjustments / ON-RRP — through auctions) Rates. Higher risk entails that the market should price these rates at higher levels. However, under the Floor system, the Fed maneuvers these rates above their respective market-determined counterparts to effectively implement Monetary Policy.

By setting a target FFR, the Fed signals its intention to conduct open market operations. Financial markets, which are speculative in nature, react before the fact or “price in” the event. Bond yields adjust in anticipation of the upcoming mass buying and selling of securities signaled by the Fed’s target.

Combining Direct Monetary Policy Tools — The Floor System

Until 2008, no interest was paid on reserves, but the Required Reserve Ratio was around 10%. As a result, banks sought to minimize the Excess Reserves they maintained. The monetary environment was described as a “low reserve regime,” the conditions of which directed the Fed’s policy implementation strategy in tandem with an expansionist agenda. The 2007/8 financial crisis impelled a policy change to drum up liquidity in the financial system.

Reserves now stand at around $3 trillion (peaking at $4 trillion at the end of 2021). The proportion of commercial bank assets held in cash has increased dramatically since excess reserves began earning interest. This has also enabled the Fed to adopt a 0% Required Reserve Ratio and enable greater monetary flexibility.

In the early days, prior to and shortly following 2008, the Fed operating what was called a Corridor System for Monetary Policy. The effectiveness of the Corridor System and modern Floor System can be understood in the context of the state of the supply of reserves:

- X-Axis: Money Market Rates.

- Y-Axis: Supply of dollar liquidity (cash or reserves).

- The blue S-shaped demand curve represents banks’ demand for reserves.

- The vertical line represents the supply of reserves at any given time. It is vertical because ultimately the Fed decides the quantity of reserves on its balance sheet.

The diagram above illustrates that the price (rate) elasticity of demand for money is high when there is excess liquidity in the financial system. As the supply of reserves decline, demand becomes less sensitive to changes in money market rates.

Demand at or below the IORB is elastic and becomes more inelastic above the IORB. This is because banks maintain deposits for two reasons:

1. They are obligated to for regulatory or operations requirements.

2. To earn the IORB.

The Corridor System

Under a Corridor System represented by the chart on the left, when the supply of reserves is low, the demand curve steepens. Banks are less sensitive to changes in money market rates. Appetite for reserves behave as a function of necessity rather than incentive.

In both systems, the Discount Rate still behaves as a ceiling to the target FFR range, with the IORB acting as a floor — however under the Corridor system it acts as a hard floor.

Hence, it is possible for the Fed to set the IORB to 0% and still effectively carry out policy implementation. A minimal reserve environment ensures the banks are more likely to engage in the Fed Funds Market hence the EFFR shifts with smaller changes in supply.

Liquidity is static when banks are maintaining reserves and rises when reserves are being loaned out. Hence the efforts of banks to minimize their reserves does not actually result in an overall fall in the monetary base.

Fed Open Market Operations (buying and selling bonds) under the Corridor System are more effective in adjusting the supply of reserve balances to move the EFFR close to the target.

The Floor System

The diagram on the right reflects the current scenario — an ample-reserves regime where the supply curve sits the right against a flat demand curve. In this highly liquid financial system, EFFR is not as volatile as reserve balances change. The Fed’s Open Market Operations are hence not as effective.

Reliance on administered rates increases. The IORB must be set close to the target rate as demand adjusts precisely to the return on reserve balances. This is because there is little incentive to holding excess reserves and the opportunity cost must be offset by the IORB. If the Fed did not pay interest on reserves in an ample reserve environment, reserve balances would fall with banks moving their funds elsewhere in the money market.

Rates are set precisely to meet banks’ demand for reserves at the Fed’s desired levels. Open Market Operations then supply reserve balances to steer interest rates toward the target range. If the EFFR falls, banks are more likely to maintain reserves in this environment. A 0% reserve requirement allows all reserve balances to be available to seek the best market rate.

Financial Institutions that are not banks are not eligible to maintain reserves and earn the IORB, but they do lend to banks in the Fed Funds Market, increasing the availability of funds and driving the EFFR below the IORB.

The Fed’s rate setting policy is very effective in today’s environment. Capital tends to flow out of risk assets and into money markets when rates are hiked and vice versa when rates are chopped as is reflected by the S&P in the context of the FFR. We will address the wider economic implications of liquidity being pulled out of the system later.

There are other tools in the Monetary Policy toolkit which involve foreign counterparties. These include liquidity swaps with foreign central banks, Repo and Reverse Repo transactions with foreign financial institutions, international monetary authorities (FIMA).

But I’m exhausted so no dice. Here are some useful links in case you are gagging for more:

https://bpi.com/category/monetary-policy/

https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy.htm

Take the Bike

In a bear market, risk asset holders tend to shift their attention to macro. Dependable ol’ Janet — like that girl Salinger knew, never could quite turn heads like J Po. He’s just the apple of your eye when your holdings are twisting in the River Styx.

Right now, everyone knows who’s holding the launch codes.

Hopefully by now we have learned that capital flows from money markets to risk assets and vice versa are largely guided by this little Infinity Stone called the US Fed funds rate.

This is the bottom line: interest rates rising and falling relative to expectations is the cardinal concern of financial market participants. So, it serves to check on how the yanks are faring with their homes, jobs, groceries etc. I hope they sleep well at night knowing every speculator in the world is concerned about their well-being.

At his Jackson Hole speech, Lord Chairman — with more gusto than his usual indeterminate innuendo — said the Fed has to do more “damage to the demand-side” of inflation.

Here’s what he meant:

Like a Box of Chocolates

The standard measure of inflation is called the CPI or the Consumer Price Index — a basket of goods and services representing the cost of living for your average broseph.

The CPI has been criticized for being a backward-looking indicator not reflecting the current state of the world, as well as other issues accounting for its inaccuracy:

Housing: Include rents but not home prices (largest component of the CPI)

Substitutes: Will use cupcakes instead of cookies (whichever has become less expensive)

Commodities: Includes energy and agricultural goods

Commodities are the most volatile components and commodity prices are largely supply-driven. i.e. oil prices moon because of wars in the Middle East (rare as it sounds), OPEC tightening the valves; while agri-goods do so because of drought, locusts etc.

Hence, the Fed likes to look at Core CPI or the PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) to really zero in goods and services with more conducive price elasticities.

This is what his Czar-man Powell meant by damaging the demand side. Currently, the Ukraine War and post-COVID supply chain issues have been the main price drivers. His Holiness has been rubbing the shit out of that Infinity Stone this year. Bumper rate hikes. And they’ve done bugger-all to temper inflation.

The market took the Jackson Hole speech as particularly hawkish, suggesting the demand-side damage (rate hikes) would have to compensate for supply side pressure.

…then around a trillion dollars fled from equities.

Let’s recall what happens when the economy is expanding, there’s more liquidity sloshing around for banks to lend out into the economy, and the cost of goods and services is rising (assuming interest rates don’t change):

Firstly, high inflation hurts savers. You stow away $1,000 into a savings account or treasury bond. If yields stay the same, that grand buys you less stuff next year. The real value of that saving goes down.

Conversely, inflation benefits borrowers by reducing the cost of servicing existing debt fall in real terms. Let’s say broseph took out a $1 million loan last year to buy a new pad. His mortgage payments run $5k a month. That pad is worth $2 million today, but his mortgage stays the same. His wealth (equity) goes up.

Now lets say broseph’s boss thinks he’s renting a feral studio under the train tracks and can’t keep up with rising rents. So, he gives broseph a raise. To accommodate that raise, he raises the price of whatever his company sells. Broseph gets more cash, goes out and splurges on goods and services — the price of which go up with higher demand.

Inflation begets inflation.

When it gets out of hand, J Po comes in and starts hacking at it with his monetary policy tools and pulling money out of the system — assuming he succeeds — let’s revisit what happens:

- Borrowing becomes expensive.

- Mortgage payments go up (likelihood of defaults rises).

- Saving money is incentivized — i.e. investment in money markets / treasuries.

- The consumption of goods and services falls.

- Unemployment rises.

- The economy slows down.

We can see that since the gold standard was done away with, spikes in inflation have been soon followed by rate hikes. Generally, the Fed targets an inflation rate of around 2%, which is considered healthy.

Assume the Fed is Leo DiCaprio and inflation is his girlfriend.

Consumer Price Index = Leo’s bae’s age

1.5% — 2.5% = 21–25

Currently, the CPI is between 8% — 9%. To the Fed, that’s like shacking up with Betty White.

Another spanner in the Fed’s fight to control inflation is that by nature, prices tend to be sticky. For example, Broseph Pizza Co might raise the price of a pie because mozzarella got more expensive. When mozzarella prices fall again, wily chef Broseph may figure ‘well let’s just keep the extra margin.’

Everything we’ve discussed so far — the dollar, monetary policy, inflation, unemployment all links up to dictate the ebb and flow of something called the Business Cycle, measured by output (or GDP).

Time to take a trip back to that hangover on day 1 of Econ 101 and look at what GDP consists of:

GDP = C + G + I + NX

C = consumption.

G = government spending.

I = investment, and

NX = net exports.

Government spending consists of fiscal stimuli (COVID cheques, tax breaks etc.), so before we move onto the trade component (NX), lets nail down the key factor within consumption and investment (C & I):

Real Estate:

The tangible, usable, ubiquitous, finite $340 Trillion asset class. The only major piece of the world’s balance sheet that isn’t a social contract dreamt up by us clever monkeys. Real Estate. In the US, 71% of household debt is represented by the good ol’ mortgage. It is the cheapest of all forms of credit. And the packaged version — The Fed itself has got about $3 trillion of MBS on its balance sheet as mentioned earlier. QE was effectively incepted to support the housing market / housing backed debt in the economy.

The bulk of all household savings are represented by the household itself. US house prices have almost doubled in the last decade. It is generally considered an inflation-protected asset, and the only way to get rich according to many a podcaster.

If the property market pukes, well, just have a reminisce about all that it covered in chunder in 2008.

To grasp its importance, it helps to think about how many economic components actually go into building a house. The raw materials encompassing a good chunk of the periodic table. The multitude of supply chains — manufacturing, logistics, distribution, labor etc. These components drive inflation (representing 10–15% of GDP on average) and are very sensitive to interest rates.

We’re going to break up housing into two components — the real economy and mortgages. The production and trade of housing units gives us a picture economic activity surrounding this market.

In the US, new home sales for the month of July came in at just over 500,000 units. This is half of what they were a couple of years prior (during peak COVID at that).

Remember, during COVID, supply chains were mangled, and real estate — which relies heavily on them — was exploding. This compounded the explosion in housing prices. We’ll get to this later.

Home sales figures directly impact housing starts, i.e., the number of new construction projects undertaken. If that number slumps, it reverberates throughout the economy, impacting the price of everything from lumber to kitchen appliances.

Fun fact — Lumber is the ultimate leading indicator for all other commodities. It is quick to react to changes in both demand and supply and is accepted as a very accurate sign of things to come. Lumber prices are currently in freefall.

The third factor sitting in between home sales and housing starts is housing inventory — the number of homes sitting on the market unsold. High levels of inventory relative to sales tends to squeeze prices. The July home sales figure represented around 11 months’ worth of existing inventory. Unsold homes are stagnant stores of value which exacerbate cash flow constraints for economic participants.

Falling home prices have much the same impact on your average broseph. The largest slice of the average American household balance sheet is the home. Two-thirds of these homes have active mortgages against them.

Back in the day in the 70’s and 80’s, US Debt to GDP hovered below 40%. At the same time, you had this boom in housing driven by baby boomers’ hitting their prime and thinking homeownership was the dog’s bollocks. This was real, demographics-propelled real estate growth.

Fast forward to the noughties, real-estate was at it again. This time, it was structurally different. The mortgage industry had become a backyard bazaar with home-loans churned out like battery chicken 3-at-a-time to pizza delivery boys and strippers with no money down.

Compounding this was the fact that banks were boxing up the loans with pretty investment-grade rated bows and moving them off their balance sheets faster than they could originate new ones.

A post Glass-Steagall monster with a feverish appetite for real estate drove prices to unsustainable levels. When rates went up in 2007, the wave of defaults was epic and sliced straight through all the poor liquidity thresholds and over leveraged capital structures in the banking system. Unemployment and bankruptcies followed.

Today, the industry is a far cry from the barely regulated, feral mortgage and securitization industries from 15 years ago. There is structural integrity in credit markets. It isn’t easy to get a mortgage and there is an onus on metrics that judge repayment capacity.

The current housing boom is however, still not predicated on fundamentals. Nor is your average broseph unduly levered. Real wages are lower, and the new generation doesn’t see homeownership as a badge of honor.

So, what’s caused housing to bubble up again?

Firstly, you may not buy a house, but you gotta live in one. Rents are a core component of CPI and importantly, represent the yield on a real estate asset. The mantra that real estate is the holy grail of investing has sprouted new windows of exposure.

Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), though have been around for decades, have gained popularity over the years — allowing the liquid trade of the coveted asset class as listed equities. Real Estate crowdfunding platforms now hold trillions in fractionalized property investments. Airbnb has spawned an entirely new class of buy-to-let investing.

Due to this idea that real estate only appreciates in the long run, investors tend to be less reactive to movements in capital prices. Property investors tend to be evangelical about building their asset book and are reluctant to sell as long as their cash flows (net rental income less mortgage payments) remain positive.

Plus, in parts of the US, the tax breaks for property ownership are astounding. Landlords can deduct for depreciation on their property, irrespective of whether it’s gone up in value. This has, in part lead to more and more institutional players entering the space. Among others, Blackstone — the world’s largest private equity fund — has been on a residential buying romp over the last decade.

And supporting this trend — our old friend the Fed. The cheap credit and liquidity in the economy, this time around, has found its way to investors, who account for more and more of overall homeownership. The people actually living in those homes — less so.

Mortgage rates have risen from 3% to 5.5% in the last year. On average, a 1% increase in the rate on a 30-year mortgage increases your monthly payment by around 10%. But household balance sheets remain strong, and mortgage payments as a percentage of income are manageable. Things can, however, turn on a dime. Balance sheets weaken with lower asset values. The ability to repay a mortgage or pay rent is, well, entirely predicated on the assumption one remains employed.

The $5K broseph is forking out for his 150sqft Brooklyn studio is set to tumble one way or the other. But the housing market does not have to fall through the floor this time. Certainly not to the same extent. And even if it does the fallout will not echo that of 15 years ago. The real issue is the reverberation of a housing slowdown to all its dependent industries. Across supply chains that stretch across a globalized world. That is where the gears shift and take us to another point in the cycle.

Benji’s World

We began this Macro Cheatsheet discussing the dollar. This is where we circle back — with the trade (NX) component of GDP. For this, we venture out of the United States, to where double-digit inflation is the present norm. Recall that the US Dollar is the reserve currency of the world thanks to (1) Bretton Woods (2) petrodollar (3) US generally being the big wolf with the big fat war-chest.

So, what happens to everyone else when the Fed starts hiking rates:

- Demand for dollar / dollar denominated assets goes up

- The value of the dollar goes up relative to other currencies.

- Trade flows decline:

- Stuff the US produces becomes more expensive.

- Selling to the US eats into producer profit margins.

Let’s quickly get through a few concepts to understand how the dollar and monetary policy impact other countries.

Balance of Payments is a record of cashflows in and out of a country. It consists of:

- Current Account: Accounts for any transactions that result in direct cash flows to and from the country including the exports and imports, remittances, income or dividends paid or earned from abroad etc.

- Capital Account: Accounts for any transactions that create assets or liabilities for the country including the purchase or sale of US Treasuries, Foreign Direct Investment (asset sales), the issuance of dollar bonds, reserve balances etc.

If the current account records a net inflow of cash, the excess cash is used to purchase investments.

If the current account records a net outflow of cash, the shortfall is funded usually by debt.

If there is an imbalance in the above, cash reserves usually make up the balance, which are usually held in US Dollars (over 50% share in global FX reserves). i.e., if a country registered a trade deficit of — $300 but raised debt (issued a bond) of only + $200 to cover it, the resulting — $100 shortfall could be debited from the country’s FX reserves.

Now let’s see what the effect a strong dollar has on trade:

Remember that the petrodollar ensures all trade for crude oil is dollar denominated. Hence crude oil and the dollar have an inverse relationship. If the dollar strengthens (its buying power increases), the price of oil falls.

All commodities are pretty much denominated in dollars (with the notable exception of Australian wool). Hence if a country is importing, it is paying dollars. A strong dollar increases the cost of buying commodities.

In reality, funds that come into a country are converted to local currency to be utilized in the economy. A strong dollar means any outstanding dollar-denominated debt becomes more expensive to service. Repayments and interest are in dollars while the income generated to service the debt is generated in local currency.

Once again, if you’d like to sink your teeth deeper into this topic there is yet another excellent explanation from the still excellent Khan Academy.

Emerging Markets

Whether a country runs a surplus or deficit does little to dent demand for dollars. Surpluses get converted into dollar-denominated assets (treasuries or other securities) and deficits get financed through the issuance of dollar denominated debt (bond issuances, IMF, etc.).

A strong dollar results in fiscal constraints as a local currency-denominated budget is squeezed by dollar denominated trade.

There are however benefits to maintaining a cheap currency. China — the world’s largest exporter — benefits immensely from its exports being competitive. This has been the core reason for the tremendous growth of its economy.

China’s sustained surpluses have been used to purchase US debt (of which it is now one of the largest holders).

The strong dollar is also accountable for the rise of offshore manufacturing — and the migration of industry from developed to emerging markets. These young economies benefited from the lower cost they offered on factors of production.

Lately, commodity producers have benefitted from global supply chain disruptions caused by COVID and the Ukraine crisis. This has driven up prices resulting in windfalls for producers.

Energy and foodstuff exporters hold plenty of dollar reserves. While country’s running deficits are seeing their currencies devalue and reserves dwindle. Some have struggled to service their debt with the notable example of Sri Lanka which defaulted on its dollar bonds earlier this year.

Murica

The dollar’s status as a reserve currency means it tends to maintain its buying power. As a result, the US is almost always running a trade deficit — they import more than they export resulting in dollar outflows. These dollars however simply come back in the form of capital.

Petrodollars behave as interest free loans in the form of reserves and US Treasury holdings. US Treasurys up to 5 years in tenor have no coupon (fixed interest) meaning the US effectively pays no interest on its short- and medium-term debt.

The dynamics of the dollarized global economy have been changing as of late. The US is now the largest oil & gas producer in the world having tapped up its shale reserves (although it still maintains a trade deficit).

Recently, we have seen supply side shocks see the price of commodities rise in tandem with the dollar. Usually, commodity prices move inversely to the dollar. The Fed is busy raising rates and strengthening the dollar without denting inflation in commodities. The difficulties faced by certain nations are hence exacerbated.

Ready Your Forks

Remember we learned that Cash money — the benjis in your pocket, the boodle in your bank account, comes into being largely through the magic of the Money Multiplier.

So, what is the M2 supply at today?

Roughly $22 trillion.

And right before COVID?

$15 Trillion.

How about during the 2007 shitshow?

$7 trillion.

Suddenly that decade long blitzkrieg of cheap money and jacked asset prices makes sense…

The Federal Government’s debt load today stands at about $28 trillion. A $3 trillion budget deficit was registered in 2021 — cumulatively, it will run over $15 trillion for the next ten years according to the Congressional Budget Office. This too needs to be financed through debt.

If the dollar were to lose its reserve status, and all that free capital were to stop flowing in, it would likely become impossible for the US to service its obligations.

Crypto… anyone?

You wouldn’t be wrong to think it’s incredible the dollar is so damn strong considering the money supply expansion. The Fed prints money ad-infinitum, and what they print remains valuable. The global economic system just seems to be designed to reinforce US spending power.

Add to that, under the ample reserve regime, the Fed has adapted its toolkit — a whole new set of (very effective) levers to control the money supply, temper inflation, while preserving impunity to draw shekels from the ether.

It all works because:

The banks have enough dollars.

The whole world wants more dollars.

Uncle Sam has enough dollars to force everyone to need more dollars.

Rinse. Repeat.

You always hear the numbers don’t make sense anymore. They aren’t normal. Remember how nuts a $800 billion bailout sounded in 2008. Chump change today. Trillions may turn into quadrillions and bazzillions. Of course it seems unsustainable it can’t be that the Fed has figured out perpetual growth. But hey, its working. We keep going, as long as we cycle there.

But right now, there’s a chemical confluence of factors suggesting that this dip in the cycle is going to cause an unopened parachute level hard landing. Its going to be a hell of a time to make money. That’s what this page is for. This article was intended to provide scaffolding.

I remember my old man told me a story from back in his school days. There was a kid in his science class. Special kid. Bless. Rocked up to the science teacher and proclaimed he had solved the energy crisis.

“its quite simple.” He said. “Just take half the electricity from a power plant, and use it to power another power plant. Then do the same with that power plant. Then again, and again.

Tesla must be kicking himself in his grave.

Sure, this kind of ignores the basic laws of… well, mathematics. But maybe he was onto something. Apparently, he went on to do great things. Now what was his name again…

Ben something

Ben B..

Bernank..

Bernie Madoff?

One of them anyway.

So that does it, hope it was relatively noob-friendly. If you’re not a noob, hit me up with observations — any faulty info, flaws in logic, counter-arguments etc. Would be much obliged.

If you’ve absorbed this, hopefully you are now better equipped to understand the wider climate for investing decisions. Go on and scare the shit out of that shylock financial advisor who’s been flogging emerging market ETFs — earning himself fat spreads, talking about GDP growth and literacy rates like a noob parasite. Not your blood noobie, not anymore.